The Galway Bog That Changed The World Not Once, But Twice

Charlie Connelly wanders among sheep in rural Connemara to find the field that once was at the cutting edge of transatlantic communication. Along the way, he discovers the origin of the term "lynch mob."

Of all the attractions of Galway, it was an old and disembodied wall that stayed with me most vividly as I drove out into the peaks and lakes of Connemara. Tucked away in a narrow lane at the heart of the city, there’s an ancient, grey stone wall that stands alone like a piece of forgotten theatre scenery. Above a brick arched doorway, there’s a glassless stone window frame through which, as I stood beneath it on my nocturnal visit, I could see the full moon. It’s not a famous landmark or even a particularly attractive piece of architecture, but the fascination lies in the story behind it.

At the end of the 15th century, the Mayor of Galway was James Lynch, whose son, Walter, was a popular man around town. Walter had lost his heart to a local beauty named Agnes, but a handsome charmer from Spain set his cap at fair Agnes. Walter engineered an argument that ended with a dead Spaniard. When his son confessed to the murder, James Lynch, as town magistrate, felt he had no alternative but to ignore local pleas for leniency and give the death sentence to his own flesh and blood.

A large crowd gathered at the gallows bent on preventing Walter’s early demise. Instead, Lynch took his son to an upper window of the family home, tied a rope around his neck, fixed the other end to a metal bar and pushed him out. I’d stood watching the moon through what’s said to be the very window beneath which Walter had kicked, clawed, and choked out his final moments. The hoodwinked crowd at the gallows left us with the term ‘lynch mob’ even if that original gathering was there to prevent an execution rather than administer one.

UNEARTHING THE ROOTS OF MARCONI’S WIRELESS REVOLUTION

"Nestled between the Atlantic and the mountains, Connemara’s bleakly yet beautiful terrain has retained an otherness born of isolation."

As I drive out of the city the next morning on the N59 Clifden Road into Connemara, I think about how the tale embodies this part of Ireland and much of what lies ahead of me: a subversive mythology based on fact and local events that have an immortal global legacy.

The drive west from Galway is one of the best in Ireland. Nestled between the Atlantic and the mountains, Connemara’s bleakly beautiful terrain has retained an otherness born of isolation. Most of Connemara is Gaeltacht, an Irish-speaking region, and the language is spoken beautifully here. It rises and falls like the landscape itself and is as lilting as the babble of its springs and rivers.

The transition from bustling city to isolation is both sudden and immediately calming. I pull over more than once to kill the engine and take in the landscape and silence. After a leisurely hour and a half, I reach Clifden, Connemara’s main town. A combination of twee gift shops and inviting pubs on the right side of tourist trap. Clifden is probably worth an hour’s amble, but I’m not making this journey to explore towns. Anyway, I have somewhere I want to see: an obscure patch of bog land just south of the town that changed the world not once, but twice.

Many places are held up as having changed the world. Some claims are dubious at best, but when I turn off the road onto a track and leave the car at a locked gate with a paint-sloshed sign that shouts "NO QUADS," I head out to somewhere that genuinely deserves the epithet.

"The Derrygimlagh bog may seem like the end of the world, a geologically turbulent, marshy backwater where black-faced sheep watch your every move, but its legacy is remarkable."

The Derrygimlagh bog may seem like the end of the world, a geologically turbulent, marshy backwater where black-faced sheep watch your every move. But its legacy is remarkable. This patch of tussock, puddle-flecked ground hosted both the first commercial transatlantic wireless communications and the landing of the first ever nonstop flight across the Atlantic.

Two minutes from the car, I’m among some lugubrious sheep on a flat patch of old concrete that clearly is the foundation of an old building. Had I been here a century earlier, I would have been at the busy centre of the cutting edge of global technology. There were once massive buildings here and a railway line, as well as a constant stream of engineers, scientists and stenographers. After dark for miles around, people could see strange flashes in the sky and hear cracks and booms that broke open the night. It’s all long gone now, though, and I am standing on all that remains of where the first transatlantic commercial wireless messages were exchanged, thanks to Guglielmo Marconi.

In 1905, Marconi, half-Irish and a direct descendent of John Jameson of whiskey fame, arrived in Ireland looking to build a telegraph station needed to swap direct messages between Europe and North America. Derrygimlagh, it seems, was perfect. When construction finished in 1907, the world’s first transatlantic telegraph message was fired through the ether to Cape Breton on 17 October. The telegraph station must have looked like the most fantastical thing in the world. It had eight masts more than 61 metres high and stretched wires half a mile across the bog. Six tall chimneys belched smoke and there was even a narrow gauge railway on which steam locomotives puffed back and forth.

On a grey and windy 21st century day, it’s hard to picture the sheer industry that went on here as I stand toeing coarse grass away from hunks of concrete. All that remains of the complex is what burned down in 1922 during the Irish War of Independence. I look across to the white stone obelisk, a hundred yards away, and think about the second world-changing event to which this patch of land played host.

A TRANSATLANTIC FLIGHT INTO THE HISTORY BOOKS

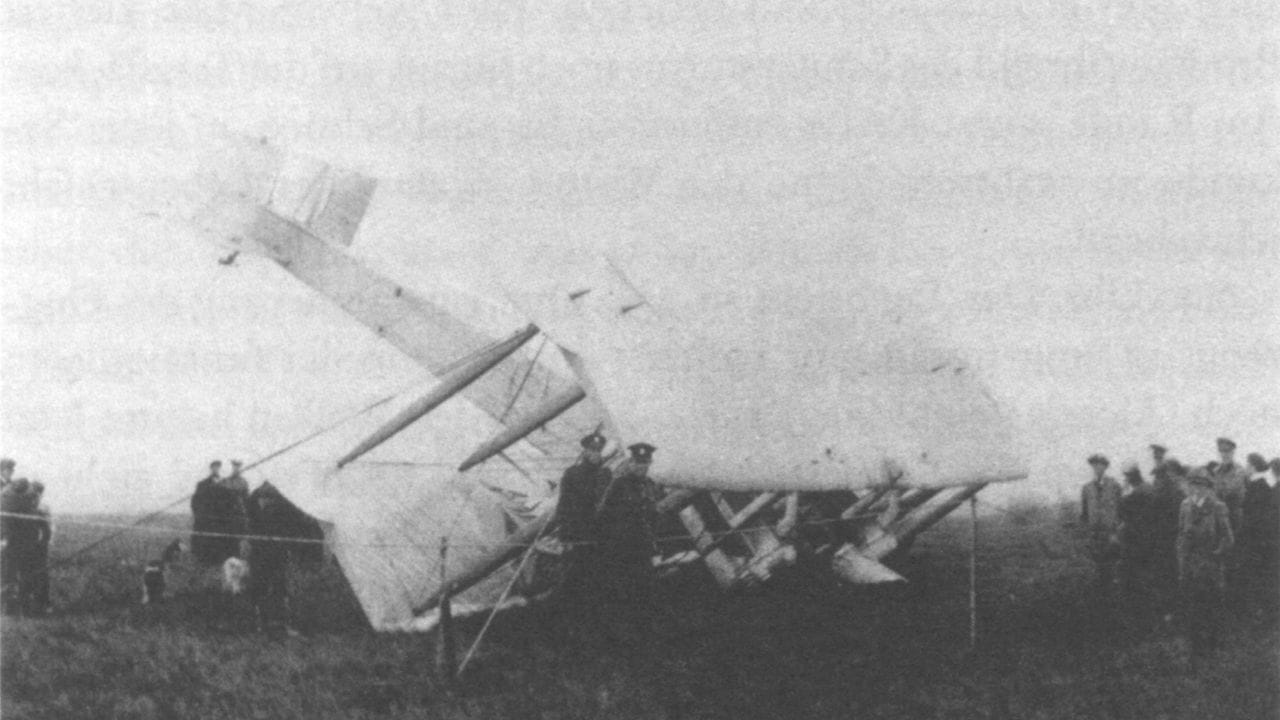

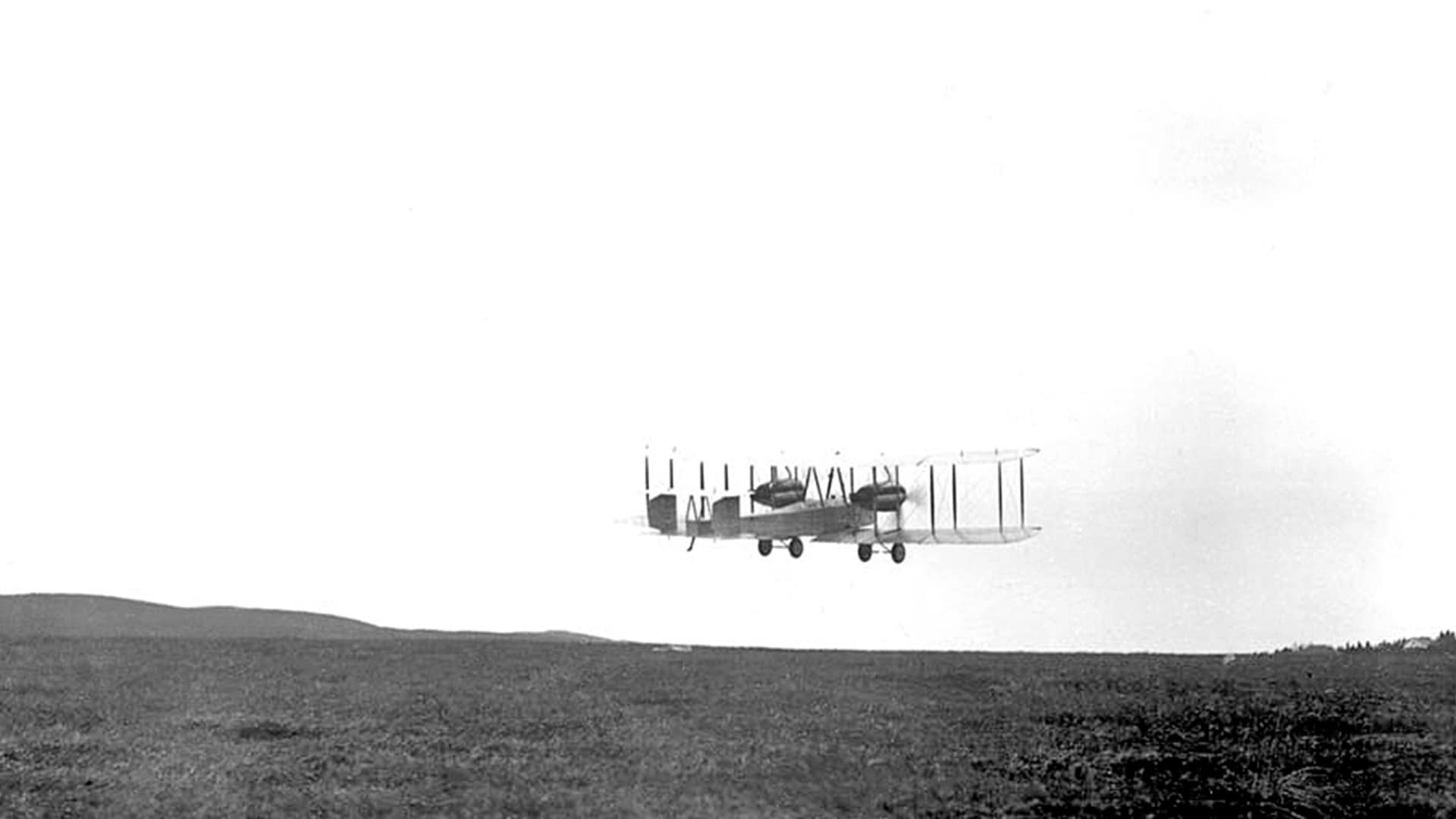

On the morning of Sunday 15 June, 1919, a distant and unfamiliar buzzing noise was heard in the Atlantic sky off Derrygimlagh. It grew louder into the throaty roar of an engine and a flimsy looking biplane appeared out of the fog. It circled, banked and executed a frankly undignified crash landing that left the aircraft with its nose in the mud and its backside in the air. A couple of Marconi’s telegraph operators ran towards the scene, from which two men hopped out and walked briskly toward them. The bigger of the men called out, “I’m Alcock, just come from Newfoundland." His colleague, Lieutenant Brown, added, “Now that is the way to fly the Atlantic.” Alcock and Brown had just pranged their plane nose first into the history books. In the space of barely a decade, this anonymous patch of Connemara bog had brought Europe and North America together as if the two continents had slammed shut across the Atlantic.

FROM THE SKIES TO SKY ROAD

After dark, for miles around, people could see strange flashes in the sky and hear cracks and booms that broke open the night.

A little weighed down by the enormity of this technological legacy, I seek relief by driving back through Clifden and turning onto the famous Sky Road, looping around the peninsula for eight exhilarating miles high above the Atlantic. After the scudding grey skies of Derrygimlagh, the sun emerged to render the ribbed waves a deep blue all the way to horizon. From there it was back onto the N59, passing the postcard-friendly turrets and battlements of Kylemore Abbey, looping around Killary Harbour, and north into County Mayo.

Although this whole drive can be done in around three hours, I’d arranged to break the journey and spend the night at Delphi Lodge, a nineteenth-century hunting lodge and the scene of one of the most heartrending tragedies of the Irish Famine. In 1847, hundreds of starving paupers died on the road here in search of food and poor relief, having walked sixteen miles in foul weather from the nearest town.

Today, Delphi Lodge is such a peaceful, beautiful place, it’s hard to imagine such a tragedy happening here. On the edge of a lake overlooked by a trio of looming mountains and popular with salmon fishers, the lodge feels deliciously cut off from the world: there’s no phone signal and there’s not a television in the place. Everyone eats together at a large dining table and whoever makes the largest catch of the day earns the right to sit at its head. That person was not me: I can barely hook a goldfish at a fairground, let alone wrestle a salmon ashore with rod and reel.

Invigourated by the peace and solitude of Delphi, I set out north again the next day along the R335 to Louisburgh, an hour’s drive during which I don’t see another soul. It’s just me, the hills and the lakes. Turning east, I skirt the southern shore of Clew Bay and pass Croagh Patrick, the pilgrimage mountain up whose rocky slopes thousands of devotees scramble each year. Some are barefoot in their devotion to Ireland’s patron saint.

I pull into Westport, regular victor in Ireland’s surprisingly popular annual Tidy Towns competition and voted Ireland’s Best Place to Live in a recent national poll. My journey complete, that evening I head for Matt Molloy’s pub feeling calm and refreshed. Molloy is the flautist in one of Ireland’s most enduring musical exports, The Chieftans, meaning the nightly traditional music sessions are of the highest quality.

A session is in full flow when I arrive and after a while, I ask one of the fiddle players if he knows Lynch’s Window. I don’t know if there’s even a tune called Lynch’s Window — I learn later there isn’t — but he nods and launches into a reel that the other players all join. As the music picks up pace I raise a glass to poor old Walter. I think he’d have liked it here.