The Big Red One: A 3,500km Outback Adventure

The dingo pads through the fiery red sand, approaching the rudimentary shelter at the rest stop on the way to Kings Canyon. It doesn’t seem to be in a baby-stealing frame of mind. It’s 44 degrees Celsius, and it just wants what we’ve got — a place to sit down and escape the sun for a few minutes.

You quickly learn that such wildlife encounters become the norm on a road trip across the Australian Outback. Big, frighteningly muscular red kangaroos can be found hopping around outside dusty opal mines. Lackadaisical herds of feral camels — which are rounded up and sent to Saudi Arabia, so prized are they for their disease-free meat — amble across the highway. Inquisitive emus strut around outside roadhouses. And there’s the ever-present, menacing grace of the wedge-tailed eagles flying overhead.

The initial idea was to see Uluru, the giant red monolith that has been a go-to symbol of the Outback in decades of Australian tourism marketing campaigns. But simply flying in seemed like cheating. Dropping in from above could never properly give a feel for the isolated remoteness. After all, part of the point is that it’s in the middle of nowhere. Why not pop by on the way from Adelaide to Darwin?

Well, the obvious answer is that doing so is borderline masochism. The Adelaide to Uluru leg is 1,595km, with another 1,959km to go before reaching the Northern Territory’s capital. And in between the two is a whole lot of glorious nothing.

Just Deserts

The desolation-dusted horizon goes on forever, and the sky seems bigger than anywhere else on earth. The South Australian desert is somewhere to feel very small indeed.

Port Augusta, three and a half hours’ drive north of Adelaide, marks the point where it all turns a bit "Mad Max." Before then, it’s all sun-yellowed pastures and world class shiraz-conjuring vineyards. Afterwards, it is brutally stark gigantism, in equal parts mind-blowing and intimidating. It should, by rights, be phenomenally boring. It is mile after mile of scrubby saltbush and spinifex, unrelentingly parched. But every small crest on the Stuart Highway unveils a panorama that makes up for lack of distinguishing detail with sheer magnitude. The desolation-dusted horizon goes on forever, and the sky seems bigger than anywhere else on earth. The South Australian desert is somewhere to feel very small indeed.

Signs of life are extremely sporadic. It can be 250km between roadhouses, the glorified petrol stations offering ultra-basic accommodation and reliably grotesque food. And when there’s a settlement any bigger than a roadhouse, it tends to be freakishly weird.

For the bulk of the journey up to the Northern Territory border, it’s open road, glare from the giant salt lakes and inexplicably addictive monotony.

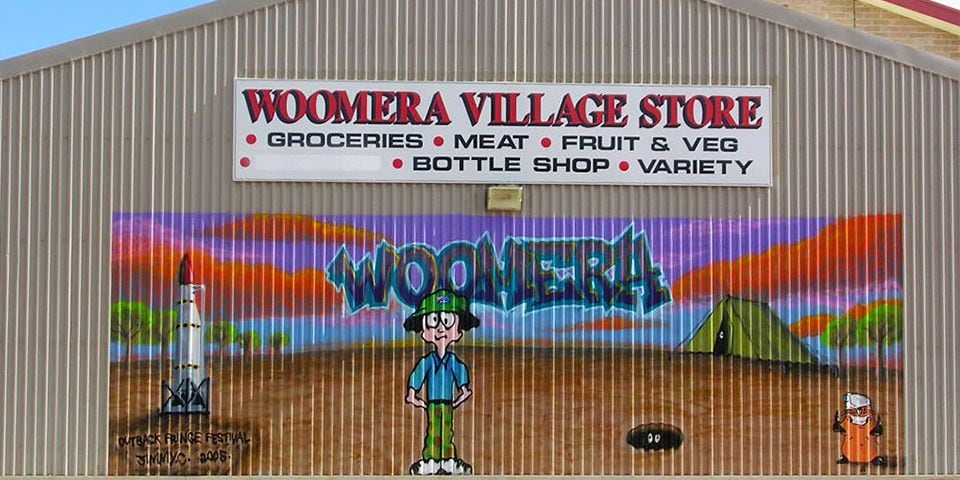

The first of these is Woomera, the existence of which was kept secret for decades. Set up as a military town, it has long been a hub for weapons testing. The Stuart Highway passes through the Woomera Prohibited Area, and straying from it is both illegal and highly ill-advised. Rockets and missiles are still fired into it, while no one quite knows what remnants there are from the nuclear bomb tests carried out in the 1950s and '60s.

The visitor centre — which plays host to what is surely the most remote bowling alley on earth – has some highly sanitised displays on Woomera’s contributions to the world of science. Oddly, they seem to focus on wholesome space research rather than weapons that could bring about an apocalypse. The lawn outside the town’s school is far less subtle — it offers up all manner of decommissioned missiles, rocket launchers and tanks to clamber over. What better way to educate the local children about their heritage?

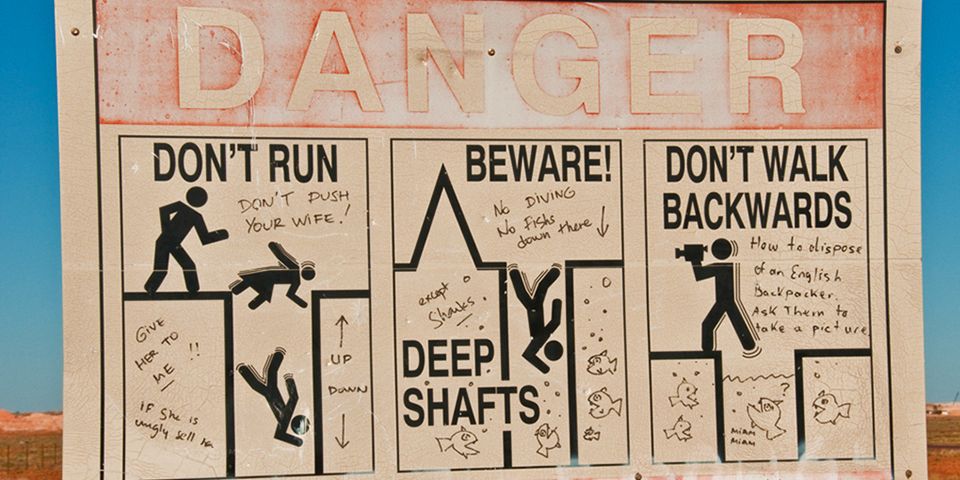

Ramping up the bizarre quotient even further is Coober Pedy, where it’s so fiercely hot, most residents decide to live underground. Most of them are miners — the bulk of the world’s opals come from around Coober Pedy — and they simply blast homes out of the rock with homemade explosives. Tours of the show homes reveal them to be surprisingly luxurious warrens, delving several levels deep, and often morphing into a mine at the end. And, for those who want to make their own fortune, there are massive rubble heaps just off the main street. Plenty of opal fragments can be found in there — it’s just a case of sifting through with increasingly grubby hands to uncover them.

But such outposts are the exception, rather than the norm. For the bulk of the journey up to the Northern Territory border, it’s open road, glare from the giant salt lakes, and inexplicably addictive monotony. A different style of driving kicks in. Speed limits are laughed off given the rightly assumed lack of policing; an ability to continually invent new games as entertainment becomes more important than keeping an eye on the road; strategies for overtaking the monstrous three carriage road trains are argued out in fine detail.

Ayers & Graces

After so much nothing, a great big something has significant novelty value. And the extraordinary thing about Uluru — one of the most hyped natural attractions on earth — is that it turns out to be underrated.

Up close, the singular image of it that everyone has stored in the brain is shattered. The colours shift as the day goes on, and the walk around the base reveals startlingly different looks every few metres. It’s a magical beast of crags where vegetation gamely tries to eke out an existence, blackened streaks show where the water pours down after rain, and caves emerge that look like savage pockmarks. A few signs on the way briefly explain the local Aboriginal Dreamtime stories, but there’s the feel that far more is left unsaid. People have been meeting, performing initiation ceremonies and teaching vital survival skills here for tens of thousands of years. The big rock has an aura that oozes this undocumented heritage.

Amongst the photogenic, intensely red dirt, there are signs that we’re out of the true desert. Plants are more densely packed together, and the occasional hardy tree makes a break for the sky.

Water, water … anywhere?

Everyone signs up for the evening barbecue, bellows along with the pub rock cover band and gets roaringly drunk enough to ignore the massive spiders in the cabins.

These changes continue on the journey north. The landscape gets greener, the air stickier, the termite mounds more prominent as the Tropic of Capricorn is neared, then crossed. But the weirdness quotient still remains pleasingly high at the overnight stops. Wycliffe Well claims to be the UFO capital of Australia, and the roadhouse owners are milking this to the high hilt by covering the premises with cut out models of little green men.

Daly Waters, meanwhile, is home to a tremendous Outback pub covered in tattered underwear and globe-spanning banknotes donated by previous patrons. Everyone signs up for the evening barbecue, bellows along with the pub rock cover band and gets roaringly drunk enough to ignore the massive spiders in the cabins. Daly Waters also marks the end of the great nothing. During the last legs of the journey through the Top End, the landscape is taken over by one thing that has been conspicuously missing for more than 2,000 kilometres: water.

At Katherine Gorge, chunkily rugged sandstone walls clamber above the pleasure cruise boats and canoes attempting to navigate the Katherine River. In Kakadu National Park, the waterfalls are ferocious in the wet season, then dainty in the dry. From the top of the rock art-daubed escarpments, vast floodplains unfold a lush green carpet underneath. And on the Yellow Waters billabong, four metre crocodiles lie in wait, ready to capture and devour any buffalo foolish enough to come down for a drink.

After a fortnight driving through the wide open and absurd, Darwin comes as a shock — how do you deal with roundabouts again? What are you supposed to do at traffic lights? And the Stuart Highway, the sole artery running across the continent, peters out into the web of city streets.

It’s an outrageous anti-climax until we pull over next to the Timor Sea, and see just how filthy the car is. The mud, dirt and dead flies tell of the adventure far more than the milometer can.